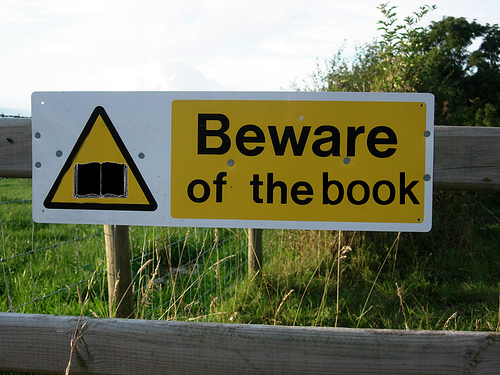

Four Reasons Why You

Shouldn't Let Yourself Get Ruffled Up By Bad Reviews

Indie published Author L. Joseph Shosty opens up about his experience with

negative reviews, how he's learned to handle them and the advice he would give

to fellow authors.

More advice exists for coping with

and combatting rejection than probably any other subject concerning the craft

of writing. Once, articles

with titles such as “Ten Ways to Survive That Rejection Letter” or “How to

Write Characters That Defy Rejection!” were prevalent in industry

magazines. Other topics,

such as how to write or even how to edit, were overshadowed by what can really

only be called a subculture, one that was about accepting and overcoming being

told no. Why? Because, statistically speaking, the

sheer number of would-be writers out there who never saw print, and would

eventually give up, were far in excess of those who would eventually be

published.

Today, things are different. Print-on-demand, self-publishing, and

e-publishing have opened up dozens of new doors. More people are seeing print than ever

before. The ratio of the

eternally rejected to published authors is more balanced. Virtually anyone can see print, in

fact. It’s not so much a

question of if you’ll get published, it’s a matter of when and in what form

you’ll do it.

This, however, presents a brand new

problem for writers. The

Internet, which has been the driving force behind the new wave of publishing,

has also bridged the gap between author and reader so keenly that virtually no

distance between the two remains. Feedback

now comes at the speed of light, and readers are obliged to become

critics. Online booksellers

encourage readers to rate and review books on their websites, in fact. Bloggers regularly review books as

part of their routine. Some

sites, in fact, are totally devoted to book reviews. And of course, you have online book

lover communities, like Shelfari and Goodreads, which use social media to

connect readers like never before. This

doesn’t sound like a bad thing, and it’s not. So, where, do you ask, is the problem?

The problem exists with the

writer. Most of the advice

out there, as I’ve said, is about how to handle rejection. Little is said, however, about what

happens after you’ve punched through the editorial wall and gotten your work

out there for public consumption. What

happens when you get a bad review? What

does getting a bad review mean? How

do you cope? This article

will hopefully answer some of those questions.

It’s better to be

professional and demonstrate an ethical backbone. A critic has just raked your book over

the proverbial coals. You’ve

gotten three one-star ratings on Goodreads with absolutely no explanation from

those who rated you. You’re

upset and frustrated. You’ve

poured everything into this book, and now people are practically wiping their

backsides with whole chapters. When

this happens, you’ve got to keep your cool. I’d like to be like other writers and

tell you a bad review is not personal, but we both know better. Your book is an extension of

you. Every writer puts a

little of himself in the things he writes. There’s a reason why we refer to our

stories as babies. We

create them, we nurture them, and we send them out into the world. If someone doesn’t like our baby, we

take offense. I’m not

saying don’t get angry or upset. That

would be telling you to go against human nature itself. No, I’m saying stay professional.

Professionalism is like currency for

writers, currency that can win them both fans and the esteem of others in the

industry. Editors and

publishers whisper amongst themselves, talking about who is impressing them and

who is an utter crackpot. They

also look carefully at a writer’s public persona and weigh it when considering

whether or not to publish that writer’s work. Will the writer treat people with

respect and dignity, thus bolstering the publisher’s image in the process, or

will the writer engage in online flame wars and otherwise stir up

trouble? Though a writer’s

personality and sense of dignity are indeed small factors compared to skill and execution, with such

things being equal, the smart money will always fall with the writer who can

keep his cool and represent both himself and his publishing house in a positive

fashion.

What does this mean? It means don’t lash out at the

critic. Don’t stalk them or

send angry emails. If the

review is posted to a site like Goodreads or Amazon, don’t get your friends or

family to write glowing reviews to counterbalance the bad. Similarly, don’t get others to rate

your books. Don’t ghost

review or rate your own, either. You

should never be doing this, anyway; it’s highly unethical. Such things skew results artificially

in your favor and it looks tacky. Personally,

if I see a writer has rated his own book, I don’t buy anything he’s

written. Check out a few

online discussion groups, and you’ll see I’m not the only one.

There’s no such thing as bad

press. A review,

good or bad, gets your name out there. It

gets a discussion rolling. The

more press your book gets, the longer its shelf life. It also doesn’t hurt to have good and

bad reviews for a book. It

shows that people are reading and really thinking about what you’ve

written. Tons of

positive-only reviews start to feel like a marketing strategy and can turn off

some readers. On the other

hand, online arguments between two people with conflicting viewpoints are pure

gold. The point is that

every time you are mentioned by anyone else, in either a good way or a bad way,

you have just gained the chance to move another copy and perhaps create a new

fan. I know by now its a

tired cliché, but take the Twilight books as an example. The people who hate these books are

legion, yet Stephanie Meyer continues to laugh all the way to the bank. Why? Because what the people who hate the

books (and who subsequently wish they would magically go away) don’t understand

is, every time they utter “I hate sparkly vampires” or some such, they are

keeping the conversation alive. You’re

probably no Stephanie Meyer in terms of book sales, but the same rules apply to

your body of work.

And for indie authors who have to do

most of their promoting by themselves, I recommend you look for sites that post

reviews not only to multiple sites, but also look for the ones that publish

honest reviews. No matter

what these critics might say, the fact they’re circulating your name and your

book will help you immeasurably.

Critics are both human and

busy. Most critics

only read a book once before writing a review. That means most of the subsequent

analysis is based on a visceral reaction to the book’s content. Much of the subtler elements, like

metaphor, allusion, and parallelism, are often lost on an overworked, harried,

and otherwise very human critic. It’s

hard for anyone to pick up on or even care that your steampunk novel makes

frequent reference to Ivanhoe, especially when there’s a deadline to meet, a

sick child to drive to the doctor, dinner to cook, and laundry to fold. Many critics, especially those with

websites like TeAmNeRd ReViEwS, are inundated with books to read,

and they must analyze as many as possible, as quickly as possible, all the

while keeping their personal lives afloat. It’s impossible for them to give you

the kind of in-depth look that you might want. That sort of analysis falls to

scholars who may one day write papers about you. Critics have another job, and that’s

to tell people what they think about a book, not fuss over its minutiae. Cut them some slack, and if in missing

your central point they also misunderstand your book and give it bad marks,

remember that they’re only human. You

would want that kind of consideration if the roles were reversed, right? Right.

Bad reviews can be helpful. On the occasions that you receive

a detailed accounting of what a person found was at a fault in your work, don’t

dismiss them out of hand. That

does you no good. This

person has taken the time to fully critique your work. Do them the same courtesy and read

what they’ve written with an eye toward improving your technique.

I’ll give you an example from my

own experience. I recently

had a story appear in a themed anthology about doomed love. Following some initial glowing

reviews, two followed which broke down the anthology story by story. Mine received a similar criticism each

time, which was that my story ended too abruptly and lacked a proper plot

arc. I was a little upset

for being singled out for criticism. The

hurt stayed with me until an editor who I greatly respect sent me a request for

a rewrite. In the request

he told me the end of the story felt rushed, saying that the final two pages

read like Walter Winchell narrating a rapid-fire denouement after Elliot Ness

and his Untouchables had taken out the gangster of the week.

I might have simply fixed the

problem with the manuscript and sent it back to my editor without giving it

another thought, but the two previous reviews had stuck with me. If the arc problem had occurred in two

stories, I reasoned, it might have occurred in others as well. I went back through my work and found

no less than six other stories with the same problem, and fixed them. If I hadn’t been paying attention to

my critics, however, there is a good chance I would not have noticed.

About the Author: L. Joseph Shosty was born in Texas City, Texas to working-class parents who divorced when he was still an infant. He spent the better part of his childhood moving from place to place, living in various parts of Texas, Louisiana, and Tennessee before finally settling in Winnie, Texas, a farming community seventy miles from Houston. He wrote his first story when he was three, but it wasn't until he was in teens that he realized his passion for storytelling could ever become a profession. He sold his first short story in 1998, and soon began amassing a following on the Internet. When his first story collection, Hoodwinks on a Crumbling Fence, was a disaster, he quit writing, intending never to publish another word again. He made good on this promise until the birth of his son, William, in 2008 prompted him to give it another try.

Where to Find the Author

No comments:

Post a Comment